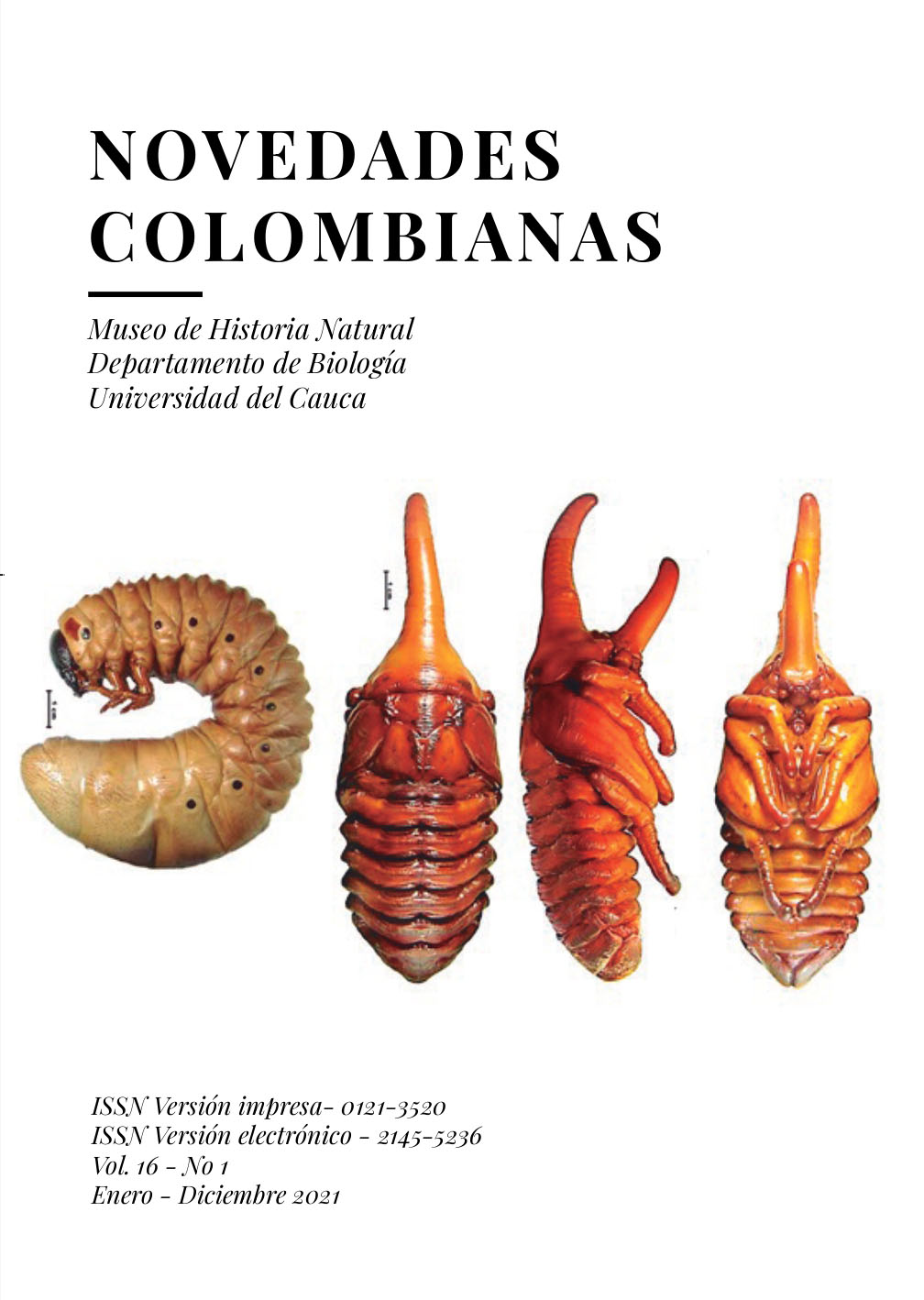

Pollination of Mucuna mutisiana (Kunth) D.C. by bats Glossophaga soricina and Glossophaga longirostris (Phyllostomidae: Glossophaginae) in the Tropical Dry Forest (BsT) in Northern Colombia

Abstract

Biotic pollination systems can be considered as an ecological process where the interaction between plants and their pollinators determines plant reproduction. It also ensures genetic variability due to pollen transfer between different plants because of cross pollination. It is estimated that bats are pollinating agents to a wide group of plants in the tropics, favoring the transfer of pollen over long distances in plants with flowers that have adaptations for pollination by chiropterans. The objective of my research consisted in describing the biology of pollination of M. mutisiana (Kunth) DC., a fabaceous plant pollinated by swee-tooth bats, in Tropical Dry Forests in the Caribbean region of Colombia. In addition to the possible incidence of the ecological role of nectarivores bats in the dynamics of the Tropical Dry Forest. The results on its phenology shows that the anthesis is twilight starting at 18:00 h. between the months of March and May; and then again October through November, with an approximate duration of 8 to 14 weeks. The maximum flower production happens between the second and third week of flowering with an average of 57 to 108 clusters; 5 to 6 mature flowers opening per night/cluster; and an average of 30 flowers per individual. It was observed that for M. mutisiana pollinisation in BsT to occur, a sudden movement is required to activate the flower opening mechanism towards the subsequent release of the necessary androecium and gynoecium for their reproduction. The flowers size is 6.3 cm (SD = 0.18; N = 25), with maximum peaks of nectar production per night of around 18.58 μl (SD = 18.74; n = 112). Maximum percentage of sugar concentration was 4.68 ºBrix (SD = 5.03; n = 112) at 6:00 p.m. Two potential pollinators bats: Glossophaga soricina (Pallas 1766) and Glossophaga longirostris (Miller, 1898), visit the flowers of M. mutisiana, with a maximum visit peak of 34.25% (SD = 39.8; n = 112) from 19: 00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. It was also observed that daylight visits were mostly made by hummingbirds (Antracotoras nigricolis and Phaetornis sp.), At night, other visitors such as opossums (Caluromys sp.) and nocturnal moths of the Sphingidae family were observed. All these observations confirmed the chiropterophilic pollination syndrome in these plant species. Its floral features of attraction and even floral rewards of M. mutisiana showed congruences between the use of the floral resource and the foraging capacity of its main pollinators, which is evidenced by contact between the anthers and pistils with the anteroposterior part of the body of the individuals of this pollinating group In the BsT. Likewise, a high value was found in the relationships that these bats have with the resources offered by the environment, given their flexibility in the diet favoring, not only the pollination systems when there is availability of nectar, but also by combining its nectarivores diet with fruits and insects, allowing these two potential pollinators of M. mutisiana to coexist.

Downloads

References

Agostini, K., Sazima, M. y Galetto, L. 2011. Nectar production dynamics and sugar composition in two Mucuna species (Leguminosae, Faboideae) with different specialized pollinators. Naturwissenschaften 98, 933. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-011-0844-6

Aguilar, R., Martén-Rodriguez, S., Avila-Sakar, G., Ashworth, L., Lopeazaraiza-Mikel, M., Lobo J.A., Marten-Rodrígez S., Fuchs E.J., Sánchez-Montoya G., Bernardello G. y Quesada, M. 2015. A global review of pollination syndromes: A response to Ollerton et al. 2015. Journal of Pollination Ecology, 17, 126–128. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.26786/1920-7603(2015)21

Aguilar, R., Cristóbal‐Pérez, E. J., Balvino‐Olvera, F. J., de Jesús Aguilar‐Aguilar, M., Aguirre‐Acosta, N., Ashworth, L. Lobo J.A., Marten-Rodrígez S., Fuchs E.J., Sánchez-Montoya G., Bernardello G. y Quesada, M. 2019. Habitat fragmentation reduces plant progeny quality: a global synthesis. Ecology letters, 22(7), 1163-1173.Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13272

Aguilar, Ramiro, Lorena Ashworth, Leonardo Galetto, y Marcelo Adrian Aizen. 2006. Plant Reproductive Susceptibility to Habitat Fragmentation: Review and Synthesis through a Meta-Analysis. Ecology Letters 9(8): 968-80.

Aldana-Domínguez, J., Montes, C., Martínez, M., Medina, N., Hahn, J., y Duque, M. 2017. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Knowledge in the Colombian Caribbean: Progress and Challenges. Tropical Conservation Science. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082917714229

Arias, E., Cadenillas, R., & Pacheco, V. 2009. Dieta de murciélagos nectarívoros del Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape, Tumbes. Revista Peruana De Biología, 16(2), 187–190. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v16i2.204

Ashman, T., Knight, T.M., Steets, J.A., Amarasekare, P., Burd, M., Campbell, D.R., Dudash, M.R., Johnston, M.O., Mazer, S.J., Mitchell, R.J., Morgan, M.T. and Wilson, W.G. 2004. POLLEN LIMITATION OF PLANT REPRODUCTION: ECOLOGICAL AND EVOLUTIONARY CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES. Ecology, 85: 2408-2421. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1890/03-8024

Baker, Herbert G. 1970. Two Cases 01 Bat Pollination in Central America. REVISTA DE BIOLOGÍA TROPICAL: 17: 187-197.

Bradshaw, H. D., y Schemske, D. W. 2003. Allele substitution at a flower colour locus produces a pollinator shift in monkeyflowers. Nature, 426(6963), 176–178. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02106

Stefan D. Brändel, S. D. Brändel, Thomas Hiller, T. Hiller, Tanja K. Halczok, T. K. Halczok, Gerald Kerth, G. Kerth, Rachel A. Page, R. A. Page y Marco Tschapka, M. Tschapka. 2020. Consequences of fragmentation for Neotropical bats: The importance of the matrix. Biological conservation, 252, 108792. Disponible en: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108792

Dunphy B.K., Hamrick J.L. y Schwagerl J. 2004. A comparison of direct and indirect measures of gene flow in the bat-pollinated tree Hymenaea courbaril in the dry forest life zone of south-western Puerto Rico. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 165(3), 427-436.

Carbone, L.M., Tavella, J., Pausas, J.G. y Aguilar, R. A. 2019. A global synthesis of fire effects on pollinators. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2019; 28: 1487– 1498. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12939

Chacoff, N. P., Aizen, M. A. y Aschero, V. 2008. Proximity to forest edge does not affect crop production despite pollen limitationProc. R. Soc. B.275907–913. Disponible en: http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2007.1547

Cusser, S., Neff, J. L., y Jha, S. (2016). Natural land cover drives pollinator abundance and richness, leading to reductions in pollen limitation in cotton agroecosystems. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 226, 33-42. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.04.020

Díaz, M. M., Aguirre, L. F., y Barquez, R. M. 2011. Clave de identificación de los murciélagos del cono sur de Sudamérica. Centro de Estudios en Biología Teórica y Aplicada; 94 pp. Disponible en: http://hdl.handle.net/11336/115357

Duffy, K. J. y Steven D. J. 2017. Specialized Mutualisms May Constrain the Geographical Distribution of Flowering Plants. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 284(1866): 20171841. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.1841.

Erdtman G. 1952. Pollen Morphology and Plant Taxonomy: Angiosperms. Stockholm, Sweden. Almqvist and Wiksell. 553 p.

Emmons, L. H. y Feer, F. 1999. Mamíferos de los bosques húmedos de América Tropical, una guía de campo. 1era edición en español. 1era edición en español. Editorial FAN. Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia.

Faegri, Knut, y L. van der Pijl. 1979. The Principles of Pollination Ecology. 3d rev. ed. Oxford ; New York: Pergamon Press.

Fenster, C. B., Scott, W., Wilson, P., Dudash, M. R. y Thomson, J. D. 2004. Pollination Syndromes and Floral Specialization. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 35(1): 375-403. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132347

Fleming, T. H., Geiselman, C., y Kress, W. J. 2009. «The Evolution of Bat Pollination: A Phylogenetic Perspective». Annals of Botany 104(6): 1017-1043. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcp197

Heithaus, E. R. 1982. Coevolution between Bats and Plants. En Ecology of Bats, ed. Thomas H. Kunz. Boston, MA: Springer US, 327-367. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-3421-7_9

Heithaus, E. R., Fleming, T. H. y Opler, P. A. 1975. Foraging Patterns and Resource Utilization in Seven Species of Bats in a Seasonal Tropical Forest. Ecology 56(4): 841-54.

Horner, M. A., Fleming, T. H. y Sahey, C. T. 1998. Foraging Behaviour and Energetics of a Nectar-Feeding Bat, Leptonycteris Curasoae (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Journal of Zoology 244(4): 575-86.

Kobayashi, S., Denda, T., Mashiba, S., Iwamoto, T., Doi, T., y Izawa, M. 2015. Pollination Partners of Mucuna Macrocarpa (Fabaceae) at the Northern Limit of Its Range: Novel Explosive Openers of M. Macrocarpa. Plant Species Biology 30(4): 272-278. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1111/1442-1984.12065

Kobayashi, S., Hirose, E., Denda, T. y Izawa M. 2018. Who Can Open the Flower? Assessment of the Flower Opening Force of Mammal-Pollinated Mucuna Macrocarpa: Operative Force of M. Macrocarpa. Plant Species Biology 33(4): 312-16. Diponible en: https://doi.org/10.1111/1442-1984.12221

Kobayashi, S., Gale, S.W., Denda, T. y Izawa, M. 2019. Civet pollination in Mucuna birdwoodiana (Fabaceae: Papilionoideae). Plant Ecol 220, 457–466. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-019-00927-y

Kobayashi, S., Gale, S.W., Denda, T. y Izawa, M. 2021. Rat- and bat-pollination of Mucuna championii (Fabaceae) in Hong Kong. Plant Species Biology, 36: 84– 93. https://doi.org/10.1111/1442-1984.12298

Liu, T., Shah, A., Zha, H. G., Mohsin, M. y Ishtiaq, M. 2013. Floral nectar composition of an outcrossing bean species mucuna sempervirens hemsl (fabaceae). Pakistan Journal of Botany, 45(6), 2079-2084.

Moura, T. M., Lewis, G. P., Mansano, V. F., y Tozzi, A. M. G. A. 2013. Three New Species of Mucuna (Leguminosae: Papilionoideae: Phaseoleae) from South America. Kew Bulletin 68(1): 143-50.

Moura, T. M., Lewis, G. P., Mansano, V. F. y Tozzi, A. M. 2018. A Revision of the Neotropical Mucuna Species (Leguminosae—Papilionoideae). Phytotaxa 337(1): 1. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.337.1.1

Muchhala, N. 2003. Exploring the Boundary between Pollination Syndromes: Bats and Hummingbirds as Pollinators of Burmeistera Cyclostigmata and B. Tenuiflora (Campanulaceae). Oecologia 134(3): 373-80. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-002-1132-0

Nassar J.M., Ramírez N. y Linares O. 1997. Comparative pollination biology of Venezuelan columnar cacti and the role of nectar-feeding bats in their sexual reproduction. American Journal of Botany 84(7):918-927.

Pallas, P. S. 1766. Miscellanea zoologica quibus novae imprimis atque obscurae animalium species describuntur et observationibus iconibusque illustrantur. Hague Comitum: P. van Cleef. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.69851

Pizano, C. y García, H. 2014. El bosque seco tropical en Colombia. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander Von Humboldt, Bogotá (Colombia) Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible, Bogotá (Colombia). 350 pp.

Sánchez, F., Alvarez, J., Ariza, C. y Cadena, A. 2007. Bat assemblage structure in two dry forests of Colombia: Composition, species richness, and relative abundance. Mammalian Biology, 72(2): 82-92. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2006.08.003

Sazima, M., Buzato, S. y Sazima, I. 1999. Bat-pollinated flower assemblages and bat visitors at two Atlantic forest sites in Brazil. Annals of Botany, 83(6), 705-712.

Schemske, D. W. y Bradshaw, H. D., Jr. 1999. Pollinator preference and the evolution of floral traits in monkeyflowers (Mimulus). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96(21), 11910–11915. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.21.11910.

Smith, S. D. y Goldberg, E. E. 2015. Tempo and mode of flower color evolution. American journal of botany, 102(7), 1014–1025. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1500163

Tirira, D. G. y Burneo, S. F. (eds.). 2012. Investigación y conservación sobre murciélagos en el Ecuador. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Fundación Mamíferos y Conservación y Asociación Ecuatoriana de Mastozoología. Publicación especial sobre los mamíferos del Ecuador 9. Quito.

Tschapka, M., y Von Helversen, O. 2007. Phenology, nectar production and visitation behaviour of bats on the flowers of the bromeliad Werauhia gladioliflora in a Costa Rican lowland rain forest. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 23(4), 385-395. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467407004129

Voigt, C. C. 2004. The Power Requirements (Glossophaginae: Phyllostomidae) in Nectar-Feeding Bats for Clinging to Flowers. Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 174, 541–548 (2004). Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-004-0442-4

Westoby, M., y Wright, I. J. 2006. Land-plant ecology on the basis of functional traits. Trends in ecology & evolution, 21(5), 261-268.

Willmer, Pat. 2011. Pollination and Floral Ecology. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

.png)